He is only called Grandfather.

Grandfather lives alone on the outskirts of the city. His wife died recently and now he struggles to take care of himself. He struggles with grief. The only joy that is still in his life comes from his 12-year-old granddaughter, Zana.

Grandfather plays dominoes with other widowers and widows in the neighborhood. He doesn’t want to remarry because that would go against the culture he was raised in. Zana wasn’t raised with the same ideas, though. She just wants him to be happy again and makes a pledge to find him a new bride. This proves to be more difficult than she imagined.

It’s a cinematic plot, described by the director as “a social drama with a comedy twist.” Valon Jakupaj directed “Pledge” during the past year and plans to release it in September.

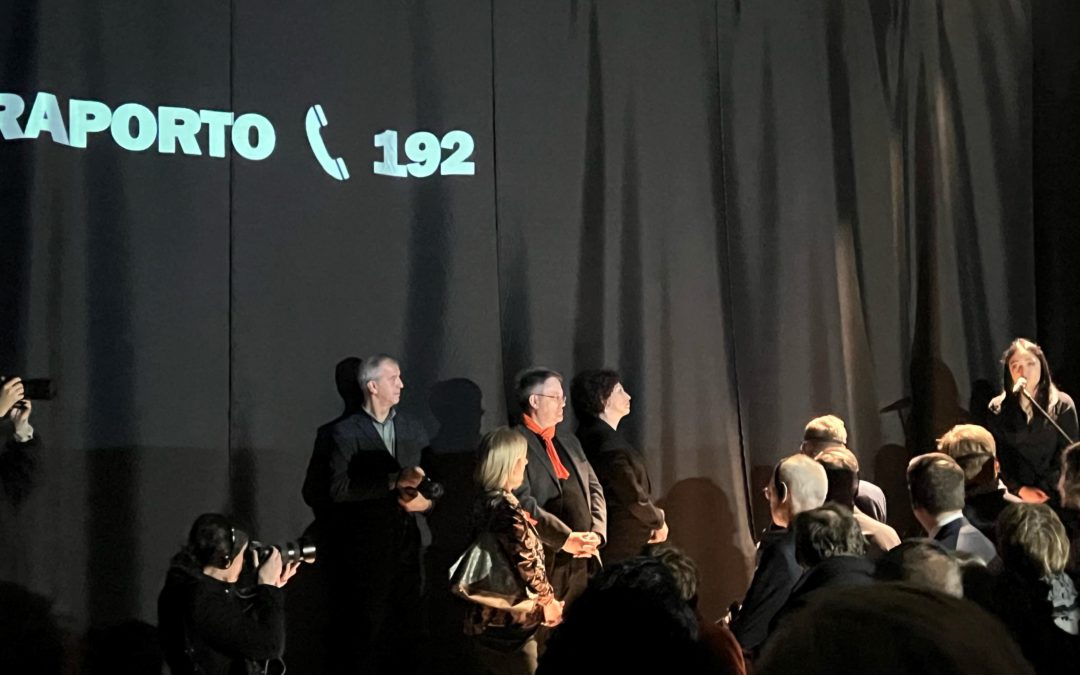

After spending more than a decade producing films in Kosovo, he knew the industry and the audience very well. But when he and his screenwriter, Dituri Neziraj, took the stage at the National Theater in Pristina last year to pitch the film to a panel of judges and an audience of hundreds, he was nervous. The winner would get 60,000 euros.

“You know a lot of people in the room. Presenting in front of someone you know, it’s a lot harder. The crowd was bigger than other festivals,” Jakupaj said.

The Pristina International Film Festival is a key part of the film scene in Kosovo. The ninth edition of the festival, nicknamed PriFest, starts Thursday. It brings in a slate of international movies for show Kosovar audiences and compete for the Golden Goddess awards. Five films from Kosovar directors will compete in the middle and feature-length categories. This year’s lineup also includes the best documentary from Berlinale, three award-winners from Cannes, and a few world premieres.

But for most people involved in making movies, PriFest is the key for the future of the industry. The Best Pitch program, which Jakupaj and Neziraj were in last year, gives upcoming directors a two-day workshop to improve their ideas and compete for a paid production. And even the directors who showing films come to improve themselves.

“Pristina is a small city and a small scene,” producer Shkumbin Istrefi said. “PriFest offers for us a huge opportunity to expand our networks and our film industry.”

PriFest was started in 2008, months after Kosovo gained independence. The two festival directors, Vjosa and Fatos Berisha, had been in the industry for a while as producers.

According to Vjosa, they were inspired by other festivals they had visited in the region but specifically by the Sarajevo Film Festival. Not only did the festival have international respect and an impressive slate of films, but it had helped improve the reputation of the city after the war.

“We had this kind of dream. When Kosovo becomes independent, we could have a festival like that,” she remembered.

The first year of the festival, Vanessa Redgrave came to Kosovo and led the jury handing out film prizes. Now the Vanessa Redgrave prize is handed out to the winners of the Best Pitch program, along with at least 60,000 euros to help finance the film and a co-producer.

Making feature films in a scene as small as Kosovo is difficult. Many directors, like Jakupaj, are in the industry for years before getting the chance to make a full-length film.

Kaltrina Krasniqi, whose film “Vera Dreams of the Sea” was also in the Best Pitch program in 2016, is one of the most established short-film directors in the country. She was one of the first students to study film at the University of Pristina when the program started in 1999.

“At the time, there wasn’t a film scene yet. It was only the old directors that were already independently producing. It was the first time the youngsters were able to do the studies,” she remembered.

The production scene was destroyed by the war, but so were the options for showing films. For years after the war, Kino ABC was the only theater in the city of Pristina and they mostly showed the big American releases.

Since then, Krasniqi has studied at UC-Berkeley, directed multiple music videos and short films, and had a short documentary shown at DokuFest. Her producer, Shkumbin Istrefi, had been in the business longer. His production company has been around since 1996 and the last feature he produced was Kosovo’s first submission for the Best Foreign Film Oscar. But even they went through PriFest and the Best Pitch program to get funding for “Vera Dreams of the Sea”.

Shkumbin said the success of the last film he produced, “Three Windows and a Hanging,” shows a larger change in Kosovo’s film industry.

“Until a few years ago, we were limited in our heads. We thought we could produce only for our market. Slowly, we became much more open-minded.”

The new generation of directors is also starting to broaden the focus of Kosovar films.

“We had a lot of films that were concerned with war,” Krasniqi recalled. “And to be honest, I think we will be making war films for a very long time. But there’s a generation that’s coming up now that is not preoccupied with it and wants to talk about other topics.”

Krasniqi’s first feature lands her within that new trend. “Vera Dreams of the Sea” is about a 64-year-old widow fighting to get control of her late husband’s estate.

In the pitch he gave at the festival last year, Istrefi focused on the reality that the film reflected. “The tradition here is that only the male family should inherit the property. It’s very interesting for the worldwide audience because it’s a tradition which is still active here.”

Although the festival is important to help the Kosovo film industry, very little at PriFest is set aside exclusively for Kosovo. One exception is the case study shown during the workshops. Berisha explains that they select a previous film by a Kosovar director to screen during the PriFORUM workshops, including the Best Pitch program. These films are chosen because they had succeeded internationally and could hopefully inspire the starting filmmakers.

In 2013, BlertaZeqiri was the case study of success. When she was attending the University of Paris-VIII for theater directing in 1997, a professor called her into his office.

“He told me directing is not a profession for women. He said, “If you apply for this you’ll only take the place of a guy that will do something,” she recalled.

Fifteen years later, she stood on stage at the Sundance Film Festival. Her short film “Kthimi”,about a couple trying to return to their normal lives after the husband spends four years in a Serbian prison,had just won the jury prize for short international films. It was the first win by a Kosovar director at a major American film festival.

“It was a dream come true but I didn’t dare dream of it,” Zeqiri remembered.

Attending the festival also helped her realize how tough it is for even the most successful Kosovar directors.

“It’s a totally different game. If you win in Sundance and you’re an American making American stories, investors will always come to you and help you. Since I make Kosovo stories, I had trouble getting investors.”

Zeqiri left the festival without a wider distribution deal. The same year, a short movie about Somali pirates called “Fishing Without Nets”won the jury prize for short filmmaking. The American director, Cutter Hodierne, was quickly picked up by Vice Films and he released a feature length version two years later. The next year, the US Short Film prize at Sundance went to a proof of concept for a feature about a jazz student and his aggressive teacher. The film, “Whiplash”, immediately got funding and was turned into a Best Picture nominee the next year.

Part of the change comes from the networking opportunities and investors at the festivals. But Zeqiri thinks that the festivals themselves can help to improve the quality of films. “How can you learn, how can you see what’s going on in the world if you only see blockbuster films?”

The production groups at PriFest can cross the most hostile of borders. The film that won the Best Pitch contest last year, “The Witch Hunter”, was a co-production between Serbia and Macedonia.

While the Serbia Film Center has never acknowledged the festival, Berisha said a lot of Serbian directors and producers come through to get help on their projects. “It’s quite important to make these connections with other countries. Through film, you see we are not different from each other.”

“A lot of new producers and filmmakers are learning that they need to get into co-productions with another country to produce their film,” Jakupaj explained.

After the Best Pitch competition last year, he received grants for his film from the film centers in Kosovo and Macedonia. That international support allowed him to move forward on the film, which he hopes will be finished by September.

Jakupaj doesn’t have an idea of what he will make after Pledge is finished. But he still plans to be active at PriFest this year and try to make new connections.

“Everybody who can should apply and attend as many workshops as they can. Even if they are not accepted, at least attend the presentation of Best Pitch. You can see what other filmmakers are saying and learn from them,” he said.

(Brennen Kauffman is a reporting intern at KosovaLive this summer in collaboration with Miami University in the United States)