The plastic Reclamation installation covering the Newborn monument was torn off last weekend to reveal the swirling designs of rivers, trees and recycling symbols once again. Newborn’s environment theme highlights an issue that is sometimes left as a last priority.

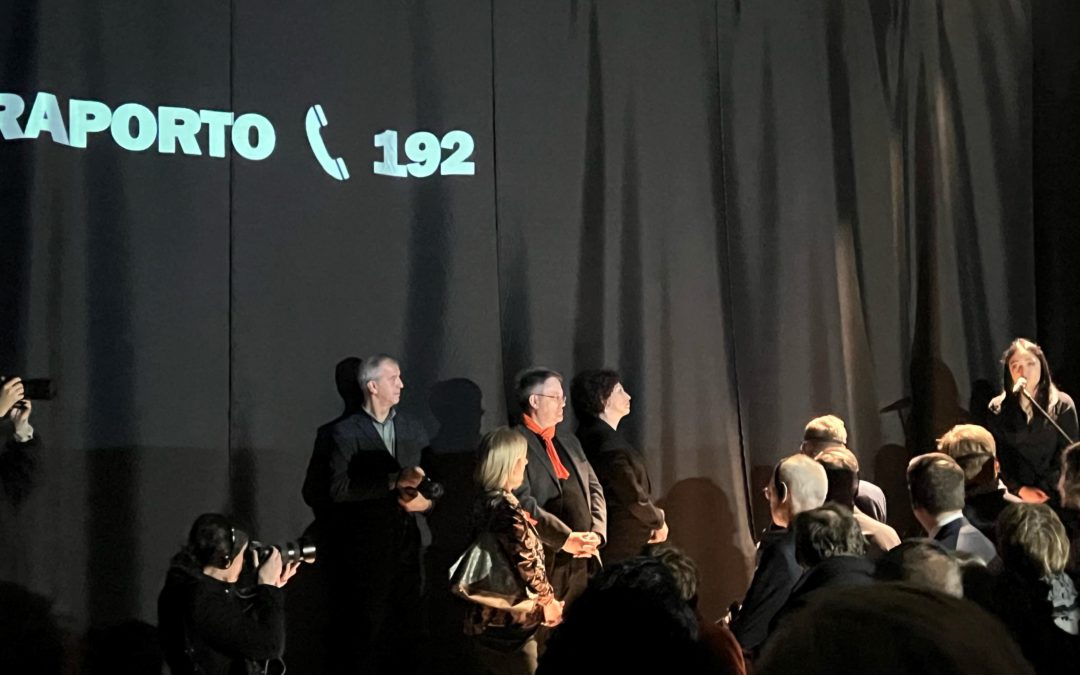

Fisnik Ismaili first revealed the Newborn monument in Prishtina, Kosovo when the country gained its independence on February 17, 2008. That day, people gathered at the site to sign their names on the yellow facade.

Ismaili and the – then Prime Minister argued after the opening, and Ismaili was not allowed to update Newborn. Five years later on the 2013 anniversary, after the monument faded with time and was buried under overlapping signatures and graffiti, the government repainted it yellow and days later, Ismaili organized 150 volunteers to paint the flags of countries who had recognized Kosovo’s independence.

Since then, Kosovar citizens are annually reminded of this day when Ismaili collaborates with the Institute for the Protection of Monuments to repaint the monument with a new theme on the country’s independence anniversary.

Nita Qena handpainted the entire monument herself last February and has been involved in the Newborn sign’s evolution since Ismaili, her husband, revealed it when Kosovo gained independence on February 17, 2008. She hoped to use environmentally-friendly paint to fit the theme, but Qena had to use oil-based paint in order for the design to handle all kinds of weather until the monument is repainted next February.

Each letter in the Newborn monument stands for a different area of environmental protection: Nature, Energy, Water, Biodiversity, Oxygen, Recycling and Nature. Beginning and ending with Nature represents the idea that every aspect is connected in a cycle.

Newborn’s annual theme reflects a new pressing issue every year. Since the beginning of the tradition in 2013, Newborn has celebrated NATO and KLA troops (2014), highlighted the diaspora (2015), tackled the issue of visa liberalization (2016), border issues (2017) and marked the 10th anniversary (2018).

However, Kosovars usually link the monument with the country’s independence, not how Ismaili or anyone else transforms it.

Flamur Kadriu, an engineer, who passes Newborn every day, mainly associates the monument with Kosova’s independence.

“When it was placed, it created that mental environment. Whoever you ask, everyone will say it relates to independence,” Kadriu said.

Next year, the environmental theme will be replaced with something else, but the country’s environmental issues are not disappearing.

According to Luan Shllaku, who is the director of the Kosovo Foundation for Open Society and in the past has worked for the U.N. Development Programme and the World Health Organization on environmental issues, some of the largest contributors to pollution are companies and Kosovo public enterprises that exploit minerals and excavate rivers.

The Kosovo government’s climate change strategy published in 2018 notes that Kosovo is believed to contain just over 166 million tonnes of collective lead, zinc, nickel and chrome reserves.

In the 1980s, mining and quarrying gobbled up 50 percent of Kosovo’s GDP, but the Kosovo War that ended in 1999 curbed this industrialization because industries were slow to be privatized. In 2011, mining and quarrying represented only 1,5 percent.

Shllaku, as well as the climate change survey, anticipates the rate of pollution from this “underground wealth” will only increase as Kosovo ramps up its industrialization. This increase combined with Kosovo’s small size will exacerbate effects.

“Within 10,000 kilometers, you have what I would call four industrial giants based on mineral exploitation,” Shllaku said.

Industrial complexes like Trepca, KEK, Ferronikeli and Sharrcom contribute the most hazardous waste out of the 1,92 kilograms of domestic waste that Kosovo generates per capita every day, which is worsened by the lack of regulated landfills and wastewater treatment facilities in most municipalities.

A 2016 Riinvest report detailing ways that Kosovo’s 16 municipalities could work together to improve environmental protections found that untreated wastewater from seven municipalities, including Prishtina, leaks into the Ibër River and ends up in the Sitnica River, which is the most polluted river in Europe. Kosovo’s Climate Change Strategy, published in 2018, classified Sitnica as a “‘dead river.’”

Diellza Gashi Tresi, Riinvest advanced researcher, contributed to the above Riinvest report, which was an unusual project for an institute whose mission is to look into socioeconomic factors.

She attributes the root of most municipalities’ obstacles to the lack of financial investment in environmental protection.

“When decentralization happened, municipalities were left on their own to deal with so many issues and they weren’t given enough, they aren’t given enough resources because the budget is limited,” Gashi Tresi said. “There is only so much they can do.”

According to the Riinvest report, specific departments devoted only to environmental protection do not exist in most municipalities. Instead, they rely on a single environmental protection officer or merge the responsibility with a department of public services that juggles multiple missions.

Because of these factors and in addition to a lack of inspectors, aging landfills fall into disrepair and the ability to enforce the protection of the environment, particularly when people and companies don’t follow protocol, is limited.

The Riinvest report also noted that a lack of awareness of environmental issues causes civilians to be part of the problem, when people create illegal landfills and cut trees illegally without considering how that affects the environment and others.

Ismaili, who is also a member of Parliament and is in a working MP group for “green” issues, believes that Newborn helps to raise awareness but acknowledges its limitations.

“I think that raising awareness is not enough, you know,” Ismaili said. “Much more should be done about this. Not only the environment, but everything else that Newborn has stood for.”

(Chloe Murdock is a reporting intern with KosovaLive this summer, in collaboration with Miami University in the United States)