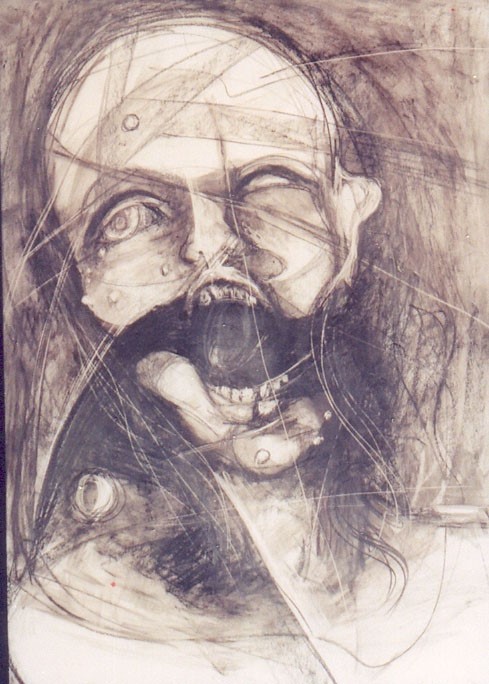

She chose to sketch this one. Out of the scratchy, wayward graphite lines, a human likeness emerged. A face wrapped in pain, the jaw detached from the rest of its head by a winding black stripe, and the eyes colorless and looking up, as though screaming silently to whatever was above it.

Zake Prelvukaj is one of many modern artists in Prishtina, where she has lived her whole life. In 1998 she created this sketch to depict the trauma that was endured by Kosovar people at the time, and was featured in her exhibit “The Art of Resistance.”

This trauma was a common theme in her artwork at that time, and was a source of motivation for many artists in Kosovo. A 1998 sketch “X-Talk”. 1998. Prelvukaj used liquid graphite with scratches, made by a thin metallic stick.

Now, she focuses on loving life and living with passion. At 53, she looks too young to have been recently divorced, and despite becoming an internationally acclaimed artist, she has never wanted to move away from Prishtina.

“I started here,” Prelvukaj explained. “Because I am here, I have emotion. The Balkans are very provocative for artists.”

Almost 20 years after sketching tortured souls, some of Prelvukaj’s most acclaimed work now focuses on the female image. She has covered herself in blue or red acrylic and used her body to paint the canvas, and sometimes filmed it for audiences. Even though the paint stains her body for up to a week, she does it to portray female sensuality, an issue still considered taboo in many parts of the world.

Her work has transitioned into tackling a wide array of issues such as gender discrimination, political commentary, and challenging societal norms. She’s exhibited her work around the world in places such as Amsterdam, Berlin, and Washington, and teaches classes at the University of Prishtina.

“Artists are very strong here,” said Prelvukaj, “They have emotion. They feel everything. Everything here is in transition. You see it, and you have motivation to paint.”

As Kosovo has set about gainin international recognition and has moved away from socialism, many contemporary and modern artists, like Prelvukaj, have worked to capture that transition and move beyond the trauma of their past.

“Everything must stay behind,” said Prelvukaj. “But never forget. People must again live together.”

She is a professor at the University of Prishtina and regards many of her pupils as friends. Her students use a variety of mediums to create their art: sculptures, instillations, paintings, drawings, video, etc. She pushes them to develop different ways of looking at issues plaguing the world today and how to translate that in their art. The Syrian refugee crisis, domestic problems in Kosovo, political issues in the Balkans are all common topics.

But beyond that, how they see those issues playing out in the future, or how the artists wish the issues would play out, are themes in their art.

It’s not just individual artists that are using their work to comment on political issues. In 2006, prominent artist Albert Heta and architect Vala Osmani, created Stacion to encourage others to do just that. Stacion is the Center for Contemporary Art in Kosovo, a non-governmental organization that is based in Prishtina.

“The idea was to create a platform which promotes the necessity for discussion and debate about works of art that dealt with the context of the time, which, previously, were never brought forward to be discussed in public”, said Heta. “Also, to create an independent space that would be focused on providing an independent space to exhibit contemporary art”.

One of the first projects Heta and Osmani organized was a conference in 2007 entitled “Alternate Identities and Cultural Problems as Crisis Management”. The project centered on the restoration of a national identity, as Kosovo was working toward independence.

They rented a billboard in the middle of Pristina, a coveted advertising space usually reserved for politicians. During the time, the neighboring billboards were covered with signs celebrating the anniversary of the independence of Albania. In the midst of these, their sign read “Time for a New State, Some Say You Can Find Happiness There”. It was a comment on the idea that reunification will solve problems in Kosovo.

Since then, they have organized hundreds of projects and exhibitions dedicated to the promotion and development of the contemporary and modern art scene in Kosovo. Their most recent exhibition is a sampling from the American Museum of Art. It is on loan from Berlin and features drawings, paintings of famous artists including

Jackson Pollock, Peggy Guggenheim, George Kennen and Pablo Picasso. The centerpiece of the exhibit is a miniature version of the American Museum of Art, recreated on small rectangular structure place in the middle of the room. The whole thing took six months to plan.

Stacion’s exhibition space doubles as its office. It’s an old, modestly sized building tucked away in the historical part of Prishtina, just past the bazaar and is separated from the Ethnological Museum by an enclosed courtyard. When looking at it from the outside, you wouldn’t think that it was possible to fit an entire exhibit in there, but Osmani and Heta manage.

“The space here has its limits,” said Osmani. “The content, however, does not.”

The contemporary art scene has a lot of potential for promoting Kosovo on an international scale. In 2014, Kosovo sent its first representative to the Venice Biennale — one of the most prestigious venues for exhibiting modern art and architecture.

Vala Osmani talks with a patron at Stacion’s exhibit from the American Museum of Art.

The Ministry of Culture, Youth, and Sport in Kosovo has not given the contemporary art scene much recognition in the past two years. It has chosen not to send a representative to many international exhibitions, including the Venice Biennale, citing financial restrictions.

“The biggest problem is budget for us,” explained Esin Shishko, an employee in the Department of Culture. “The culture budget is only 1.1 percent of the government’s budget–roughly 4 million euros. There are different payments and costs, institutions, capital investments that need to be covered.”

The Department of Culture divides its budget into two categories. The first category goes to professional institutions that are directly administered by the Ministry of Culture. Those institutions received 1.94 million euros in funding this year. The second category is for funding individual artists and NGOs, and is about 900,000 euros less, at 1.02 million euros.

“We are not creating the cultural performances, we are supporting them with our budget,” said Sami Piraj, a deputy director in the Department of Culture. “We are trying to select the most attractive projects that are being offered from the NGOs and individual artists.”

For the past two years, Stacion has been denied funding from the Ministry of Culture for its projects. It has received some money from The Ministry of Diaspora and the Ministry of Education, but most of its funding comes from international foundations and small private donations.

According to Heta, there is no other independent organization like Stacion that deals with contemporary art in Prishtina. As such, they have worked tirelessly to fill that void for artists here.

“The existence of an independent scene signifies a functioning democracy,” he said. “It is essential that something like this exist.”

Their latest project concluded mid-July. For 15 days, “Summer School as School” featured international artists from Ljubljana, New York, Belgrade, Vienna, Oslo, Skopje, and Sarajevo. They came to Prishtina to lecture on everything from the histories of contemporary art to cinematography to curating.

Through the efforts of individuals like Zake Prelvukaj and groups like Stacion, Kosovar artists are trying their best to push boundaries with their work.

“We have good artists,” said Prelvukaj. “I have been in many states around the world. People who live in Paris are lucky. We live here. We have nothing. No help. In Paris, in Holland, the states have money. Here, the state does not have money.

Here, everybody works for themselves. Here, it is not easy to be an artist, but our artists are very strong.”

(Caroline Ford was a reporting intern at KosovaLive 360 this summer, in collaboration with Miami University in the United States.)