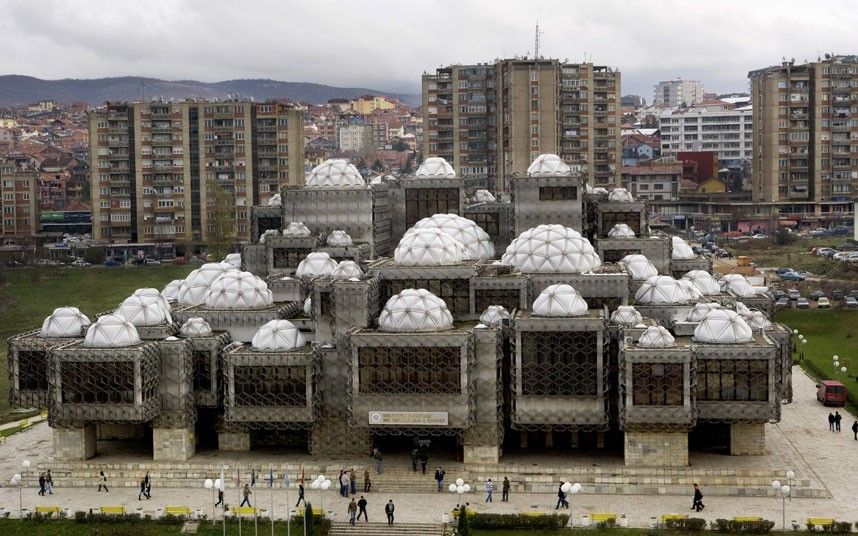

When people think of Paris, visions of the Eiffel Tower spring to mind. Sydney brings thoughts of the white, sail-like walls of the opera house, and New York City’s iconic skyscraper provide its classic look. Places are often associated with the architecture within them, and Pristina is no exception.

Pristina architects and planners are hoping to create a new, memorable image for the city. They say a hodge-podge of architecture characterizes Pristina today. But it is a city in transition, with Socialist era buildings and their dull brown, tan and off-white colors clashing with new glass facades. Historic monuments sit in squares surrounded by clothing shops and cafes.

When president of the Architects’ Association in Kosovo, Eljesi Surdulli, thinks about the architecture in Pristina, he mainly sees buildings that need to go. “Destroy and deconstruct the buildings,” said Surdulli. “Maybe most of them.”

Surdulli said the residential buildings should be taken down first because they are not structurally sound and lack aesthetics.

According to Surdulli, architecture is a mirror of the economy.

“You cannot find very much good architecture here because the economy is very low,” he said. “Good architecture needs money, a lot of money.”

Surdulli’s future vision of Pristina includes buildings with more space between them and less stories. He described residential buildings with walls the color of blue, red and yellow intermixed with historic and governmental buildings made of stone rather than cheap metal or glass façades.

Founder of the Pristina architecture firm ANARCH Astrit Nixha also had an unenthusiastic outlook on Pristina’s architect.

“We could sell it as how not to do architecture,” Nixha said.

He explained that much of the architecture built in Pristina is not regulated or held to specific standards, and often times young architects without much experience are allowed to design and construct buildings. As a result, Nixha believes Pristina’s architecture is not a representation of what architecture should be.

For Nixha, architecture and music go hand-in-hand, and he believes Pristina’s architecture began to deteriorate when music tastes began to shift.

“We used to listen to different music,” said Nixha. “When I grew up, we were listening to more British-style music. So all new wave, rock, all of British and mainstream underground music was present. The British have the style that they want to be individualists. They don’t want to follow.”

Nixha said that this type of mentality translated into architects implementing more original work.

“You had to be someone,” said Nixha. “You had to be different. You should not go with the flow.”

But after the war, Nixha said that as Kosovo began to change, so did its people and their taste in music. More mainstream media flowed in, and architecture lost its creativity.

“There were different kinds of people who listened to different kinds of music,” Nixha said. “They came in and they wanted to do different deals.”

Kosovo began to rebuild, and a demand for free space was created. Unfortunately, the supply was not there.

“This was an underdeveloped part of Yugoslavia,” explained Nixha. “And suddenly there was a need for a lot of free space. There were a lot of NGOs flooding from all around, but we did not have enough space for all of them, so we started illegal buildings. What that meant was there was not time to design.”

According to architect Visar Geci and his research with Archis International/Pristina, 70 percent of building in Pristina occurs illegally. Coming out of the war, Pristina lacked the necessary governmental bodies and law enforcement to require building regulations and inspections. The results were buildings without structural reliability and basic safety measures such as fire escapes. These inefficiencies are still with city buildings today.

“Illegal buildings are the opposite of beautiful architecture,” said Geci. “After the war, everyone misunderstand freedom. It didn’t mean you could build whatever you wanted.”

For Geci, architecture reflects the mentality and culture of the folk in that city. He believes the cheaply and quickly constructed buildings do not accurately represent Pristina and its people.

Geci said one example of this is the glass facades that have begun to make an appearance in Pristina’s architecture. Buildings such as parliament and Riljndia are now covered in shiny, steel-blue glass panels that reflect everything around them. Geci said these glass facades are a result of the government wanting Pristina to appear more modern. But he believed they only succeeded in making the city look fake.

“Pristina doesn’t have an identity right now,” he said. “If you don’t have history, you have nothing.”

However, some architects such as Bekim Ramku appreciates Pristina’s messy, unorganized architecture.

“It’s eclectic,” said Ramku. “It’s very mixed and it depends on the people. It’s something very local and having all these different types keeps it interesting.”

Ramku is the director of the Kosovo Architecture Foundation, an NGO that promotes architecture, conservation and cultural heritage to the general public through programs and festivals.

And although Ramku enjoys Pristina’s architecture, he does not deny that it has some problems. He said these problems first appeared when unqualified architects were allowed to build.

“A lot of young architects right out of school got to design, and they made a lot of mistakes,” he said.

Ramku said the biggest challenge for Pristina’s architecture lies in reversing this process. However, Ramku understands this would take a better economy, more government regulation and reforms within the University of Pristina — things he said Pristina does not have.

“The only thing we can do now is work with the public space,” said Ramku. “I think it is crucial to provide public spaces because architecture is endangered by the ignorance of people who don’t know the history, the value of these buildings. It’s important for the next generation.”

Ramku’s future vision for Pristina’s architecture involves small, cultural buildings rather than towering skyscrapers.

“A place where you can find small, tucked away landmarks that you don’t see immediately,” Ramku said. “I want it to be more than music and young people, more than night life. I want people to come for the architecture and culture.”

But future visions for Pristina’s architecture are varying.

Some architects believe Vetëvendosje is the answer. Geci and Surdulli said that Vetëvendosje, the political party known for their radical actions with tear gas and ideals of creating a greater Albania, has also agreed to fight corruption and illegal building in Pristina. And to architects like Geci and Surdulli, who believe the only way to progress architecture is a top-down approach, Vetëvendosje is the logical first step in achieving government regulations that would end illegal building.

Once government cooperation can be achieved, Geci believes that the future of urban planning in Pristina should be centered around its youth.

“Nothing in the city center appeals to young people,” said Geci. “Yes, you have the cafes and shops, but the city is still divided.”

As the youth are the future of Pristina and Kosovo as a whole, Geci said they need to be united. As such, Geci envisions Pristina’s future architecture as open and unified, where people can easily travel to all parts of the city.

Geci and his Archis International/Pristina team created the project Prishtina Dynamic City. Their vision begins with connecting the old city of Pristina to the city center. He explained how Mother Theresa will be extended across Agim Ramadani, the major street that separates the old city from the center. While the street will remain, pedestrians will have the right of way to easily walk across it into the old city.

The same idea will be implemented on the other side of town. According to Geci, Mother Theresa will stretch to the University of Pristina’s campus, opening the way for students to effortlessly make their way to the city center.

“We need to show that it’s all connected, that we have an identity,” said Geci. “We need to represent what our future should look like.”

Geci also believes the globalization of culture, and therefore architecture, will help Pristina to advance and become more integrated into European culture.

However, Nixha does not accept that.

According to Nixha, architecture’s advancement lies in individual and original concepts. He believes the globalization of culture, especially through technology like the Internet, has limited people’s ability to think and create differently. The results are buildings that do not reflect Pristina as a whole.

“You should feel the mentality,” said Nixha. “Losing a day in Pristina doesn’t mean anything. But losing a day anywhere else, you lose a job. We should represent that loose style of work, and the buildings need to reflect local craftsmen rather than factories in China.”

Nixha said what the building looks like is less important than the architect’s reason for creating it.

“Every building, if it has a proper story, is original,” Nixha said. “Globalization means becoming someone else. Greatness is being yourself and finding your personality.”

(Kierra Sondereker was a reporting intern with KosovaLive this summer in cooperation with Miami University in the United States.)