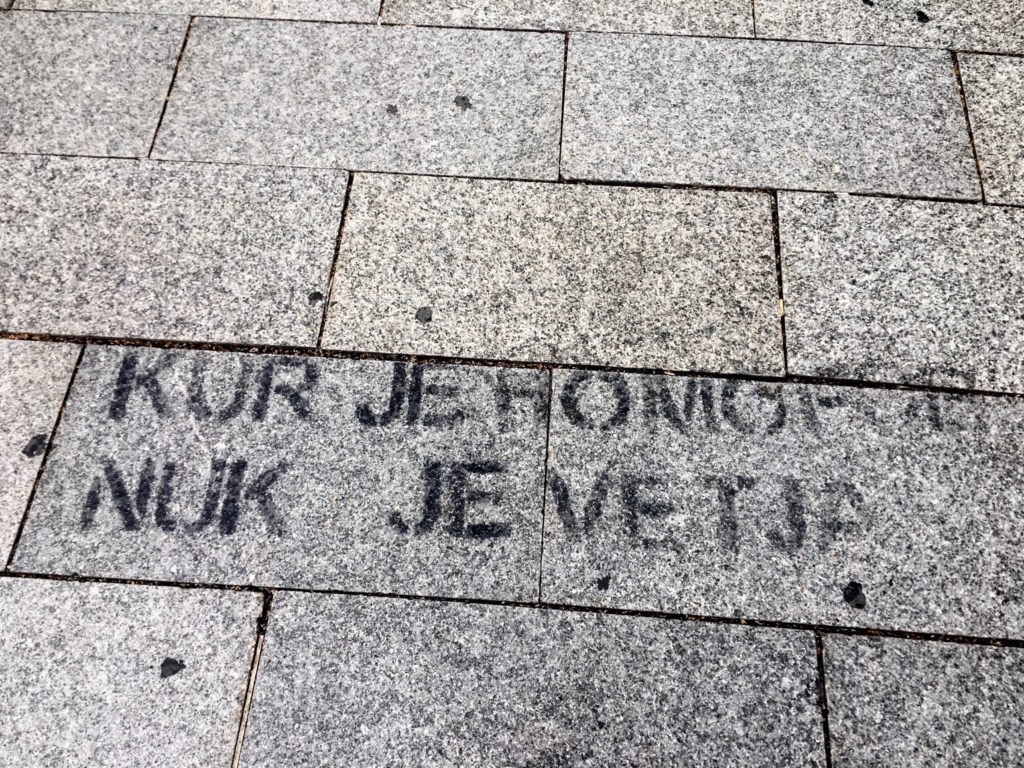

The graffiti on Mother Teresa Boulevard has faded slightly since May, but it is still legible enough. “WHEN YOU ARE HOMOPHOBIC YOU ARE NOT YOURSELF,” it declares in all capital letters, as people walk in Prishtina’s city center.

Only a few years ago, activists say anti-homophobic street art would have been unthinkable here. But does it suggest a turning point for the LGBTI movement in the country?

Lendi Mustafa, an activist formerly with the Center for Social Emancipation (QESh), said that this marks a new development for LGBTI activism in Kosovo. Unauthorized street art reflects the work of individual activists, apart from organized civil society.

The messages were painted in several locations along the pedestrian walkways near Skenderbeg Square. They appeared in the early hours of May 17 of this year, in conjunction with the International Day against Homophobia and Transphobia (IDAHOT).

IDAHOT, first observed in 2005, is recognized by the UN and has 130 nation-observers worldwide, according to its transnational organizers. And this year, organizations including the Center for Equality and Liberty (CEL) and the Center for Social Group Development (CSGD) made sure it would be observed here in Kosovo, as well.

But they were not the only ones vying for the public’s attention. According to CSGD program manager Liridon Veliu, the messages were likely part of “an awareness raising campaign,” put on by independent activists.

Although the graffiti appeared during IDAHOT, it was not part of the activities put together by CSGD or their partners at CEL. Veliu said that to the best of his knowledge, “none of the organizations that work with LGBTI rights have done the spray-painted messages in the Mother Teresa Boulevard.”

While the people responsible for it remain a mystery, the graffiti’s purpose is clear: to shift public opinion towards greater acceptance and social equality for Kosovo’s gay citizens.

Statistics on public perception published this year by the OSCE show that 44 percent of Kosovar women, and more than 70 percent of Kosovar men, are somewhat or very uncomfortable with gay men. Around half of Kosovars (64 percent of men and 41 percent of women) would be ashamed if their child was gay or lesbian.

If the street art is correct, these numbers suggest that many in Kosovo are currently ‘not themselves.’ It also suggests that any campaign against such biases will require time and persistence in order to have a lasting effect.

CEL program manager Rina Braimi sees the tide shifting, however slowly, in favor of LGBTI activism and greater equality in Kosovo. She started three years ago as a volunteer, and today she oversees a much wider range of awareness-raising activities and events.

Shortly after Braimi began her work with the organization in 2015, Kosovo saw its first anti-discrimination bill that pushed for the inclusion of gender identity as a protected class. In her opinion, however, the pivotal year for the movement was 2017, when she helped to organize Kosovo’s first Pride March in Prishtina, alongside other activists at CEL and CSGD.

This event created a greater sense of public awareness, and for many in the LGBTI community it provided the first safe space for individuals to be themselves in public. Before 2017, the community generally stayed underground, Braimi said. After 2017? “Media had more access to the community, to NGOs, to everything.”

IDAHOT festivities this year were organized for much the same reason, in order to raise awareness. The International Day Against Homophobia was originally created in order to combat harmful, shame-based perceptions of gay men and lesbians in societies across the globe. In 2009, the IDAHO committee expanded the definition to include bisexual individuals as well as the transgender community.

On May 17, organizers put on an exhibition called “Qe Pse!” in Prishtina’s city center for IDAHOT. This was a response to some members of the public asking why last October’s LGBTI Pride events were necessary. The display consisted of a diverse array of homophobic and transphobic threats and hate speech that Pride organizers had received. Among the messages were graphic slurs, death threats, and calls for LGBTI genocide and suicide.

It was met with public shock and indignation, according to Braimi, but this was not a surprise, as LGBTI activism is still relatively taboo in Kosovo.

While 67 percent of Kosovo’s LGBTI population feels discriminated against, only 11 percent of the general population of the country agree, according to a 2015 National Democratic Institute survey.

Even after last year’s Pride, many workers at LGBTI-centered NGOs still fear that discrimination, and even violence, may occur at any time.

Mustafa, a transgender activist, is a relatively well-known figure, and he says his minor fame may be has shielding him from more direct violence.

“I do get threats, and negative comments on social media, but I haven’t faced physical attack—which did happen to some other LGBT members,” he explained.

Though no homophobic violence has been publicly reported recently, Mustafa recalled one incident in 2012 where several people, though not gravely injured, were assaulted by a crowd of religiously-motivated homophobes following a panel on LGBTI-inclusive sex education in Kosovo.

Those who do not have Mustafa’s profile are at greater risk. “I’m one of the lucky ones,” he said.

Veliu said that after Pride last year, there was a surge in negative comments posted online, many of which made it into the “Qe Pse!” exhibition.

And while no accounts of interpersonal violence have surfaced, Veliu did note one incident that occurred on IDAHOT. “An old guy tried to break the exhibition,” he said, although this person only succeeded in “bump[ing] it down.”

In Kosovo’s constitution, as Braimi pointed out, “the LGBTI population is specified as a marginalized community,” worthy of equal status under the law. But many other laws in Kosovo—laws which she believes are “anti-constitutional”—have negative material consequences for people with different sexual orientations and gender identities.

For instance, Article Fourteen of the Law on Family restricts the recognition of marriage to partnerships between “two persons of different sexes,” and gender reassignment for transgender Kosovars is not legally recognized.

In addition, laws that in theory protect the LGBTI community from discriminatory practices are not always enforced by authorities, according to Braimi. A hate crime law created to codify further protections was rejected last year in the Assembly. (It may reappear in the civil code in 2018.) “The law part is a bit messy,” Braimi acknowledged, adding that she could talk about it for hours and still have subjects to cover.

CEL serves an advisory role in crafting new legislation to protect LGBTI individuals, but it and other NGOs are also active in attempts to shape public opinion.

In this context, Braimi mentioned the 2015 NDI survey, which found that only 3 percent of Kosovo’s citizens would support a friend or neighbor who was LGBTI without reservation. (Another 8 percent would still accept them but avoid the topic in conversation, and 10 percent didn’t know how to react. Thirteen percent of Kosovars admitted they would become physically violent toward an LGBTI person that they knew.)

These numbers are cause for urgency in the country, both for organizations like CEL and for individuals in the community. “When you are homophobic, you are not yourself” is a message meant to protect the LGBTI community from harm.

Braimi said that while gay couples from abroad are tolerated in Prishtina, many locals are stigmatized or ostracized for being openly gay or bi. And “that’s not to mention the rural places,” where organizers, largely concentrated in Kosovo’s capital, have only recently begun to reach out.

A new nationwide network, under Mustafa’s direction, aims to connect organizers and activists in all of Kosovo’s seven districts. “We’re working on this network where we want to go to different municipalities,” said Mustafa, now a peer coordinator for CEL, “so we could make progress in other places as well, not only in Prishtina.”

These regions are on the whole more socially conservative regarding LGBTI issues than the capital, according to Braimi. “It is accepted that there is LGBTI community in Kosovo,” she clarified, but they are pushed to the margins of social consciousness, where the most homophobic violence can occur.

For Kosovo, street art is unlikely to solve homophobia on its own. But when asked if the graffiti was a positive sign for LGBTI equality, activists were optimistic.

“It is, actually,” Veliu said. “From my personal point of view, I see it as a positive.” While organizations do not formally condone graffiti, they cannot prevent individual LGBTI people from feeling empowered to do so on their own. “The community is starting to do activism by themselves.”

Mustafa was at first measured, reaffirming that neither he nor other organizations were responsible. But then, offering a sportive grin, he made a prediction: “This year is the LGBT year for Kosovo.”

The LGBTI community is at a precarious point in Kosovo’s history, where anything could happen. But no matter what, Braimi emphasized, the recognition of gay and trans people has already spread throughout civil society: “LGBTI is everywhere. It’s everywhere.”

(Isaiah Raimey is a reporting intern with KosovaLive this summer in collaboration with Miami University in the United States.)